Tonel

b. in Havana, Cuba, 1958. lives and works in Cuba and Canada.

Antonio Eligio Fernández “Tonel” is an independent artist, art critic and curator. He graduated with a degree in Art History from the University of Havana in 1982. He taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, California, in 2001, and was a visiting artist/lecturer at the Center for Latin American Studies and at the Department of Art and Art History in Stanford University, California, from 2001 to 2003. His articles and essays on Cuban and Latin American contemporary art are frecuently published in catalogues, magazines and books in Cuba and abroad. His works are in the collections of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba; the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany; the Van Reekum Museum in Apeldoorn, Netherlands; the Daros Collection in Zurich, Switzerland; the Department of Fine Arts at the Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom; the Lehigh University Art Galleries, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; the Arizona State University Museum in Tempe, Arizona; the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida; and the Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art in the University of Texas, Austin, Texas, among other institutions.

Tonel was the recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in the Humanities (1997-1998), with residency at The University of Texas, Austin, and the John S. Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship for Painting and Installation Art (1995). He was awarded the Prize for Art Criticism by the Cuban Section of the International Art Critics Association (AICA) in 1988. In 2003 he received the Cuban Artists Fund Award (New York, USA). He is currently based in Vancouver, Canada, where he focuses on his own practice as a visual artist and writer, and teaches drawing and painting at the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

In Tonel’s works the human (Cuban) body seems to become conscious of its own odors and fluids, with a compelling sensory intensity. Unlike some of his compatriots, Tonel is not interested in deconstructing historical narratives. He is a visceral explorer who ventures into territories that are taboo in art, setting his gaze on inconsequential, everyday moments.

Antonio Eligio Fernández “Tonel” is an independent artist, art critic and curator. He graduated with a degree in Art History from the University of Havana in 1982. He taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, California, in 2001, and was a visiting artist/lecturer at the Center for Latin American Studies and at the Department of Art and Art History in Stanford University, California, from 2001 to 2003. His articles and essays on Cuban and Latin American contemporary art are frecuently published in catalogues, magazines and books in Cuba and abroad. His works are in the collections of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba; the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany; the Van Reekum Museum in Apeldoorn, Netherlands; the Daros Collection in Zurich, Switzerland; the Department of Fine Arts at the Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom; the Lehigh University Art Galleries, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; the Arizona State University Museum in Tempe, Arizona; the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida; and the Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art in the University of Texas, Austin, Texas, among other institutions.

Tonel was the recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in the Humanities (1997-1998), with residency at The University of Texas, Austin, and the John S. Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship for Painting and Installation Art (1995). He was awarded the Prize for Art Criticism by the Cuban Section of the International Art Critics Association (AICA) in 1988. In 2003 he received the Cuban Artists Fund Award (New York, USA). He is currently based in Vancouver, Canada, where he focuses on his own practice as a visual artist and writer, and teaches drawing and painting at the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

In Tonel’s works the human (Cuban) body seems to become conscious of its own odors and fluids, with a compelling sensory intensity. Unlike some of his compatriots, Tonel is not interested in deconstructing historical narratives. He is a visceral explorer who ventures into territories that are taboo in art, setting his gaze on inconsequential, everyday moments.

"Between the Moon and a Golf Ball"

at Massimo Ligreggi Gallery, Catania, Italy

Exhibition View "Between the Moon and a Golf Ball" at Massimo Ligreggi Gallery, Italy

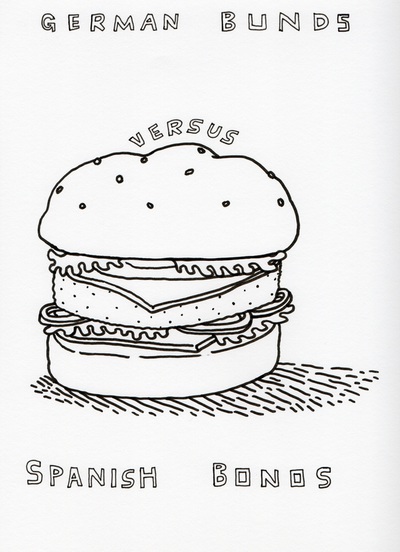

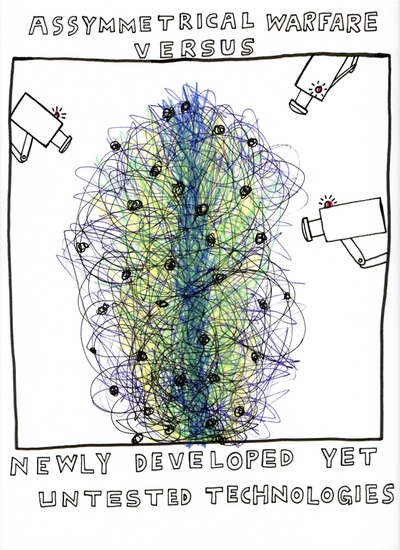

Tonel’s (Antonio Eligio Fernández) exhibition, Between the Moon and a Golf Ball. Drawings and Installations, at the Galleria Massimo Ligreggi in Catania, presents an important nucleus of works that highlights an articulated frequentation of history and memory, both collective and personal. This nucleus brings together drawings and installations that contain references and allusions to the Cold War period, between the middle and the end of the last century. And they construct an unusual representational relationship with the world.

Massaguer, to Rafael Fornés and Santiago Armada (Chago), this wide-ranging production brings with it an archipelago of questions: the themes of male and female, individual and community, the subversion of machismo (associated with the Cuban Revolution), the global economy and neoliberalism in the midst of financial crises and the vagaries of stock markets. It questions the link between scientific/material progress and ethical/moral progress, and issues related to the widespread need for security in our times, as well as the perennial formation of ‘imperialisms’.

Moreover, while the humorous and parodistic emphasis of Tonel’s drawings made with ink on paper (sometimes also with watercolour and acrylic) is in tune with the potential of genre cartoons related to the social psychology of the Cuban people and, above all, of political satire (a wide experience ranging from the character “El Bobo” drawn by Eduardo Abela, who embodied the civil conscience of the Cuban nation under Gerardo Machado, to the socio-political chronicle of the humorous supplement “Dedeté”, founded in 1969, which featured José Luis Posada, Carlos Julio Villar (Carlucho), Alberto Morales (Ajubel), and many others). On the other hand, his thematic multiverse goes beyond the field of cartoons and satire in favour of an open imaginary space-time without boundaries or stylistic labels: a space in which Tonel’s multimedia artistic practice continuously questions our mental structures. Perhaps the ironic characters of the artist’s drawings are the visual transfiguration of that Cuban oral transmission which, through “choteo”, double meanings and artificial narrative solutions, has told stories of various kinds about the vicissitudes of the island and the representation of the world. Tonel’s irreverent attitude is certainly evident, reconsidering the space of satire as an act of reflection – a position that is far removed from the usual exercise of graphic humour in vogue in Cuban magazines since the 1980s. For the artist, both the line of the drawing and the concept count (guides inherited from Chago’s subversive sign). Line and concept are indispensable to conceive visual glimpses that disarticulate schemes and shake up any form of statism. However, the commentary is not explicitly direct, but subtle and elliptical, hovering between irony and cynicism.

Another salient aspect. The scenes and characters drawn by Tonel avoid the grandiloquence with which stories are usually told. Their narrative charge, of subjective matrix, brings to the fore portraits of otherness and questioning approaches to diplomacy, power, money, the marginal or the vernacular, to the “high” and “low” zones of culture. It is a narrative vision inspired by political contexts but with a predilection for the historiographic approach. In fact, the artist, born in Havana in 1958, incorporates the (lived) experience of the “capitulation” of the Soviet Union followed by the weakening of the opposition between the US and USSR blocs. At the same time he ‘introjects’ the traumas of the ‘Período Especial en Tiempos de paz’ in Cuba in the early 1990s – a difficult time of austerity, rationing and economic cuts. (...)

Text by Giacomo Zaza

continue reading here

Massaguer, to Rafael Fornés and Santiago Armada (Chago), this wide-ranging production brings with it an archipelago of questions: the themes of male and female, individual and community, the subversion of machismo (associated with the Cuban Revolution), the global economy and neoliberalism in the midst of financial crises and the vagaries of stock markets. It questions the link between scientific/material progress and ethical/moral progress, and issues related to the widespread need for security in our times, as well as the perennial formation of ‘imperialisms’.

Moreover, while the humorous and parodistic emphasis of Tonel’s drawings made with ink on paper (sometimes also with watercolour and acrylic) is in tune with the potential of genre cartoons related to the social psychology of the Cuban people and, above all, of political satire (a wide experience ranging from the character “El Bobo” drawn by Eduardo Abela, who embodied the civil conscience of the Cuban nation under Gerardo Machado, to the socio-political chronicle of the humorous supplement “Dedeté”, founded in 1969, which featured José Luis Posada, Carlos Julio Villar (Carlucho), Alberto Morales (Ajubel), and many others). On the other hand, his thematic multiverse goes beyond the field of cartoons and satire in favour of an open imaginary space-time without boundaries or stylistic labels: a space in which Tonel’s multimedia artistic practice continuously questions our mental structures. Perhaps the ironic characters of the artist’s drawings are the visual transfiguration of that Cuban oral transmission which, through “choteo”, double meanings and artificial narrative solutions, has told stories of various kinds about the vicissitudes of the island and the representation of the world. Tonel’s irreverent attitude is certainly evident, reconsidering the space of satire as an act of reflection – a position that is far removed from the usual exercise of graphic humour in vogue in Cuban magazines since the 1980s. For the artist, both the line of the drawing and the concept count (guides inherited from Chago’s subversive sign). Line and concept are indispensable to conceive visual glimpses that disarticulate schemes and shake up any form of statism. However, the commentary is not explicitly direct, but subtle and elliptical, hovering between irony and cynicism.

Another salient aspect. The scenes and characters drawn by Tonel avoid the grandiloquence with which stories are usually told. Their narrative charge, of subjective matrix, brings to the fore portraits of otherness and questioning approaches to diplomacy, power, money, the marginal or the vernacular, to the “high” and “low” zones of culture. It is a narrative vision inspired by political contexts but with a predilection for the historiographic approach. In fact, the artist, born in Havana in 1958, incorporates the (lived) experience of the “capitulation” of the Soviet Union followed by the weakening of the opposition between the US and USSR blocs. At the same time he ‘introjects’ the traumas of the ‘Período Especial en Tiempos de paz’ in Cuba in the early 1990s – a difficult time of austerity, rationing and economic cuts. (...)

Text by Giacomo Zaza

continue reading here

"A Latin American Art Serial"

by Hans Herzog

«Ambivalence entered my work because humor, and irony especially, are so important to me. I am interested in the ambivalence of daily life. The unambiguous doesn’t attract me because there is no room for interpretation.»

Always ambivalent

Tonel appears serene, obliging, and very friendly at all times. He moves in the world with a wise and calm composure, with unpretentious discretion and urbane professionalism. I have never seen him moody or taciturn; he always seems amenable for a conversation. He exudes a certain British understatement—a far cry from Cuban clichés that embrace anything loud and overtly obvious.

Tonel converges on his artistic themes and contents in a highly playful manner, full of elegance and the type of humor that does not stop short of his own person. His works go far beyond political and social satire and always reflect their own message at multiple levels.

Evolving gradually and steadily since the 1980s to this day, his work consists mainly of rather small-format drawings. It is easy to trace the long historical tradition of all these numerous black and color-ink and pencil images back to European and Cuban “humorous” drawings—from William Hogarth to Wilhelm Busch to Santiago Armada (Chago). Tonel addresses the psychosocial constitution of the Cuban people as well as the so-called battle of the sexes, omnipresent machismo, and the supposedly «revolutionary» political attitude of his compatriots.

Beyond caricature

But it would be too short-sighted to reduce Tonel’s drawings to political satire or even caricature: they are far more polyvalent. Tonel usually holds their meaning smoothly afloat. They are frequently elliptical, full of subtle irony and require the viewer to follow his thoughts – much in the spirit of concept art, which Tonel has of course received since his youth. It is no coincidence that most of his sheets are underlaid with text, either as explicit titles or as written comments that form integral graphic components. Words and images thus mutually refer to each other and together constitute the image content.

Tonel’s drawings contain many personal dreams and fantasies as well as numerous collective, “avant-garde” socialist utopias. His graphic reflections on the subject of pop art are particularly characteristic. Entirely in the style of pop art, they at the same time reflect the pamphlet-like features of their formerly propagandistic templates, thus becoming a systemic meta-criticism of sorts. Humor, systemic and self-criticism, as well as “philosophical” aphorisms («Coito ergo sum») are the common threads running through his drawings, which sometimes take a sarcastic turn («Mal de lengua»).

So like Cuba—or not?

Tonel created not only drawings, but also installations. One of his most important works, and incidentally also one of the most emblematic works of all of Cuban contemporary art in general, is «El bloqueo», a floor work composed of concrete blocks arranged in the shape of the Cuban archipelago. The statement made with this «image» could hardly be simpler and more obvious, and yet so genuinely ambivalent, in Tonel’s sense, at the same time. The artist created the work on the occasion of the third Havana Biennial in 1989, virtually coinciding with the fall of the Berlin Wall. What followed, due to the support from the Soviet Union being ceased, was the so-called «periodo especial» in Cuba, a time of utter economic deprivation.

«El bloqueo» is the Cuban term for the U.S. embargo imposed in 1960 at the beginning of the so-called revolution that has not been lifted since. The entire domestic political legitimization of the Castrist military regime was based on this «bloqueo», which Fidel Castro and his cohorts were therefore keen to maintain throughout their lives, as it enabled them to justify all and any of their actions to their citizens.

The «bloques de concreto», the concrete building bricks that the work is made up, merge to form the «bloqueo», or blockade. However, they not only symbolize the «bloqueo» imposed by the U.S.A., although this was the «official» interpretation that secured a prominent place in the permanent exhibition of the Cuban National Museum of Fine Arts (sic!) for this work. The true meaning of the work lies in pointing out the futility of any «efforts» on the side of Cuba to build up something of its own—all endeavors have only ever led to absolute immobility, to stagnation, to rigidity cast in concrete, and to an unresolvable self-blockade. Or hang on, did we just misinterpret something there…?

by Hans Herzog | April 23, 2022

Always ambivalent

Tonel appears serene, obliging, and very friendly at all times. He moves in the world with a wise and calm composure, with unpretentious discretion and urbane professionalism. I have never seen him moody or taciturn; he always seems amenable for a conversation. He exudes a certain British understatement—a far cry from Cuban clichés that embrace anything loud and overtly obvious.

Tonel converges on his artistic themes and contents in a highly playful manner, full of elegance and the type of humor that does not stop short of his own person. His works go far beyond political and social satire and always reflect their own message at multiple levels.

Evolving gradually and steadily since the 1980s to this day, his work consists mainly of rather small-format drawings. It is easy to trace the long historical tradition of all these numerous black and color-ink and pencil images back to European and Cuban “humorous” drawings—from William Hogarth to Wilhelm Busch to Santiago Armada (Chago). Tonel addresses the psychosocial constitution of the Cuban people as well as the so-called battle of the sexes, omnipresent machismo, and the supposedly «revolutionary» political attitude of his compatriots.

Beyond caricature

But it would be too short-sighted to reduce Tonel’s drawings to political satire or even caricature: they are far more polyvalent. Tonel usually holds their meaning smoothly afloat. They are frequently elliptical, full of subtle irony and require the viewer to follow his thoughts – much in the spirit of concept art, which Tonel has of course received since his youth. It is no coincidence that most of his sheets are underlaid with text, either as explicit titles or as written comments that form integral graphic components. Words and images thus mutually refer to each other and together constitute the image content.

Tonel’s drawings contain many personal dreams and fantasies as well as numerous collective, “avant-garde” socialist utopias. His graphic reflections on the subject of pop art are particularly characteristic. Entirely in the style of pop art, they at the same time reflect the pamphlet-like features of their formerly propagandistic templates, thus becoming a systemic meta-criticism of sorts. Humor, systemic and self-criticism, as well as “philosophical” aphorisms («Coito ergo sum») are the common threads running through his drawings, which sometimes take a sarcastic turn («Mal de lengua»).

So like Cuba—or not?

Tonel created not only drawings, but also installations. One of his most important works, and incidentally also one of the most emblematic works of all of Cuban contemporary art in general, is «El bloqueo», a floor work composed of concrete blocks arranged in the shape of the Cuban archipelago. The statement made with this «image» could hardly be simpler and more obvious, and yet so genuinely ambivalent, in Tonel’s sense, at the same time. The artist created the work on the occasion of the third Havana Biennial in 1989, virtually coinciding with the fall of the Berlin Wall. What followed, due to the support from the Soviet Union being ceased, was the so-called «periodo especial» in Cuba, a time of utter economic deprivation.

«El bloqueo» is the Cuban term for the U.S. embargo imposed in 1960 at the beginning of the so-called revolution that has not been lifted since. The entire domestic political legitimization of the Castrist military regime was based on this «bloqueo», which Fidel Castro and his cohorts were therefore keen to maintain throughout their lives, as it enabled them to justify all and any of their actions to their citizens.

The «bloques de concreto», the concrete building bricks that the work is made up, merge to form the «bloqueo», or blockade. However, they not only symbolize the «bloqueo» imposed by the U.S.A., although this was the «official» interpretation that secured a prominent place in the permanent exhibition of the Cuban National Museum of Fine Arts (sic!) for this work. The true meaning of the work lies in pointing out the futility of any «efforts» on the side of Cuba to build up something of its own—all endeavors have only ever led to absolute immobility, to stagnation, to rigidity cast in concrete, and to an unresolvable self-blockade. Or hang on, did we just misinterpret something there…?

by Hans Herzog | April 23, 2022

Past exhibitions at Mónica Reyes Gallery

Robert Kleyn | Manuel Piña | Tonel | Naufragio (2016)

Getting Physical / By Keith Wallace

Excerpts from the essay written by Wallace for the exhibition catalogue

The majority of Tonel’s artwork consists of drawings, and most of them involve some form of self-portraiture; at times it is obvious, and at times not. His self-portrait functions as a kind of alter ego, and the rendering of it on paper offers Tonel a means of expression that he might not otherwise exercise in his everyday socialized life.

The drawing process gives licence to explore the recesses of the mind through traces of the body—the hand—in ways that are not contingent upon realistic transcription, it is a space where logic can lose its anchor. Tonel presents us with figures that somehow continue to function in spite of a still-bloodied amputated limb, or a useless arm that exaggeratedly extends into a shit-like pile on the ground, or a penis that enters the ground and re-emerges as a plant. Unlike a photograph, even a digitally manipulated one, his drawings are not intended to impress us with a simulacrum of reality. The body and its organic fluidity, its often messy unpredictability within the propriety of how it is expected to behave socially, find a place in Tonel’s imagination. And drawing is a venue for him to unearth anxious psycho/social states of mind that invade everyone’s inner, and often troubled, relationship with the world regardless of geography, class, or sex.

I believe everyone has thoughts they don’t readily want to admit to thinking about. Such thoughts that enter the deepest corners of our minds are not based on logic but are based on what unsettles the norms and systems that supposedly keep our lives in order, that keep us safe. Tonel explores the lack of order and logic that taunts us, and he does it, for the most part, without judgement; he makes propositions rather than proclamations.

Another element that is fundamental in almost all of Tonel’s work is language. His interest in the relationship between the image and the word has been evident from his earliest drawings influenced by both popular and political cartoons where, within this genre, a relationship between word and image is inherently a symbiotic one. Words provide a framework for a reading of the image, and, visa versa, the image illustrates the words.

Tonel’s interest in language also stems from his encounter with conceptual art and its placement of language as a central component within the workings of an artwork. The use of language in conceptual art that developed in Latin America, which was his first experience of it, was poetic and ambiguous, although often in a politicized way. Luis Camnitzer, who moved from Uruguay to New York in the 1960s, and who first exhibited in Havana in 1983, is an important link between Latin American and Euroamerican concerns. In his work, Camnitzer incorporated language in order to destabilize the meaning that exists in both the word and image. He created relationships that functioned less like the caption of a cartoon and more like two entities encountering each other within the space of an art object. Words, like images, don’t necessarily have stable meanings, but instead, can embrace ambiguity through their own necessary reasoning.

So where does Tonel’s three-dimensional work fall within the context of his drawing and its content? To begin with, it does not fit into one clear category: There are sculptures that stand independent of the drawings and portraiture; there are others that are based on the self-portraits, and then there are full-scale installations.

The relationship between his drawing, and for that matter his sketches, and sculpture follows no logic, but a relationship does exist, although the order of what would seem to come first is not always adhered to. A sketch can be made for a sculpture, a sculpture can be made without a drawing, a drawing can then be completed after the sculpture, or any order thereof. The differences/similarities between the drawings and the sculptures lie not in the norm of what should come first, but in the ways they represent. Drawings primarily involve the eye and mind; within the hierarchy of art, drawing is the workhorse, the vehicle for the evolution of ideas, and anything can happen. Drawing is a representation, sculptures are physical objects that exist in space and time, and thus bring into play the relational presence of our bodies. The installations emphasize this physicality even further in that the viewer is literally inside the artwork.

In order to understand an artist’s cosmos, one desires a kind of logic to emerge. In Tonel’s work, it’s there, but it’s difficult to locate because he keeps logic illusive. What he does in both his drawings and his sculpture is unsettle our assumptions about the way we think things should be.

i Artist Statement in catalogue for Utopian Territories: New Art from Cuba (Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery/Contemporary Art Gallery: Vancouver, 1997), 122.