Manuel Piña-Baldoquín

b. La Habana, Cuba, 1958. lives and works in Vancouver

Manuel Piña is an artist, teacher, and social and spiritual activist. His research adopts spirituality and technology as a way of expanding upon present realities and challenges. Piña is co-founder of the Newtribes School, an online and land-based global network of healers, teachers, and cultural and software activists working towards the preservation and dissemination of ancestral wisdom and language. Piña was born in Havana and graduated as mechanical engineer in Vladimir, Russia, in 1983. He began exhibiting his art in 1992. He has been a professor at the University of British Columbia since 2004, and his work has been exhibited globally, including the Havana Biennale, the Estambul Biennale, Kunsthalle Vienna, Grey Gallery, N.Y., LACMA, U.S.A., DAROS Museum, Zurich.

Manuel Piña is an artist, teacher, and social and spiritual activist. His research adopts spirituality and technology as a way of expanding upon present realities and challenges. Piña is co-founder of the Newtribes School, an online and land-based global network of healers, teachers, and cultural and software activists working towards the preservation and dissemination of ancestral wisdom and language. Piña was born in Havana and graduated as mechanical engineer in Vladimir, Russia, in 1983. He began exhibiting his art in 1992. He has been a professor at the University of British Columbia since 2004, and his work has been exhibited globally, including the Havana Biennale, the Estambul Biennale, Kunsthalle Vienna, Grey Gallery, N.Y., LACMA, U.S.A., DAROS Museum, Zurich.

Naufragios | Manuel Piña

at Surrey Art Gallery | Curated by Rhys Edwards

October 2, 2021 - May 1, 2022

Manuel Piña is concerned with everyday imagery and the way it appears in modern-day culture. His two-channel video installation for the video wall at the Surrey Arts Centre, titled after the Spanish word for "shipwreck," captures concerns about utopia, migration, and space. By editing imagery of the ocean, Piña's work reflects upon time and image-making. Over the course of the video, footage of the ocean endlessly twists and fragments. In the process, Piña creates dizzying geometric patterns. The project extends Piña’s ongoing investigation of ephemera and abstraction in lens-based media. His art speaks to force and movement in the form of wakes, ripples, and waves.

IN FOCUS | by Denise Ryner

for Backflash Magazine (2016)

Throughout much of the 15-minute duration of Manuel Piña- Baldoquín’s 2015 video work, Naufragios, the viewer’s focus is directed towards the liminal visual space where an anonymous body of water meets the sky. Even before encountering Piña-Baldoquín’s work, the viewer is already accustomed to looking towards such horizons as a point of orientation. The artist plays with this visual tendency through a series of digital manipulations, thereby forcing the viewer to repeatedly search the shifting, morphing and folding images for each new horizon.

Naufragios is the Spanish word for shipwrecked, a state of emergency and diversion from the crisscross of global commercial, exploratory and migratory routes that have been established over time. Shipwrecks can lead to the founding of new routes or represent temporary-to- permanent exclusion from the historical and universalized narratives that equate constant movement and expansion with progress. The implied temporariness of Naufragios counters the cultural associations between sea, sky and eternity, and brings the documented seascape in Piña-Baldoquín’s work in line with the series of visual disruptions and glitches that define the formal characteristics of his video.

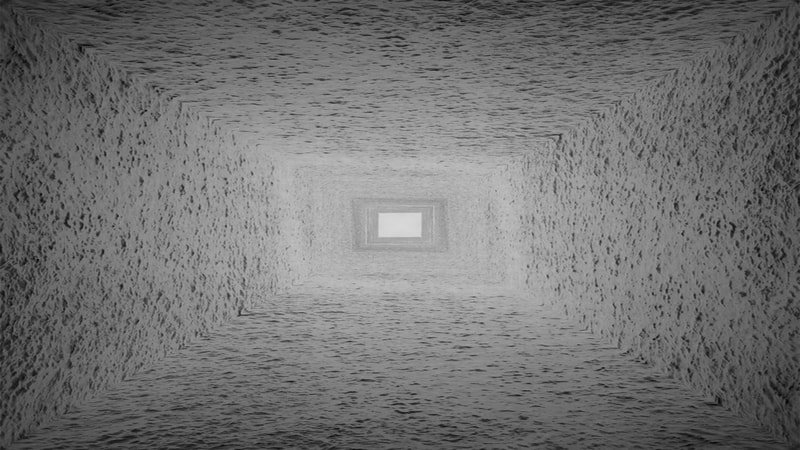

The opening frames of Naufragios feature a stable image of an anon- replacing the sky save for a narrow, horizontal, light grey band indicating the now doubled horizon. A minute or so more and the sea closes in, filling the sides so that the sky is reduced to a rectangle at the end of a watery tunnel, still pulling the eye towards it.

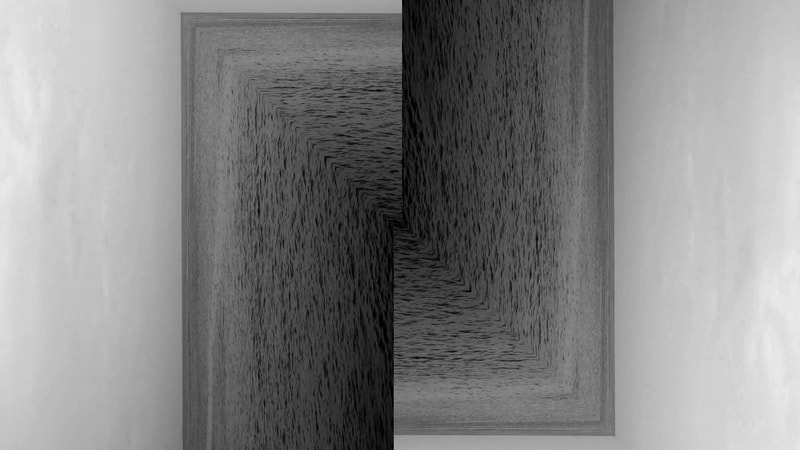

The video continues like this—now the horizon folds itself into two interlocking right angles, then expands out again to a diamond, with the horizon stretching out towards four corners and referencing the frame of the screen, which slowly overtakes the horizon as the orientating structure. Simultaneously, the time between each shifting form starts to pull away from minute-long intervals to establish a new regularity and unit of time.

The simplicity of Naufragios’ key looping image supports the ease with which Piña-Baldoquín’s forms build on each other to develop a rhythm and timecode unto themselves. The viewer slowly begins to adapt, then rely upon, this shift from the visual orientating structure of the horizon, dividing the water below and the sky above into a new orientational apparatus based on the screen and a series of layered time-intervals.

It is a common association to link water and time through the anonymous body of water. The work is silent and shown in black and white. The horizon line splits the vertical height of the frame at almost the halfway point. The overcast sky and low contrast mostly diminish the visibility of the clouds and juxtapose the seemingly calm sky with the sharp ripples spreading across the dark waters below. The exclusion of visible terrain or any other objects and markers creates a uniform symmetry between sea and sky.

This uniformity allows the viewer to easily spot the jump cuts marking the start of the ten-second loop, from which the video is built. This regular pulsing of the image serves to pull attention away from con-templation of the seascape and towards the characteristics and limits of video as a medium. However, rather than reading as failures, the jumps quickly become familiar and establish the structure of Naufragios. Despite the representations of geography in the recorded image, and the various geometries that Piña-Baldoquín creates from the seascape, it can be argued that Naufragios is a meditation on time rather than space. Beyond engaging video’s time-based qualities, its metronome- like progression proposes that the medium itself can also be a form of time-keeping.

About a minute into the video, the sea suddenly mirrors itself, daily ebb and flow of tides as markers of the passing day. However, Naufragios expands on these broad cultural givens that equate oceans and seas to spans of time, as well as immensities of space and distance. Recent and historical associations between water as a site of migration and mythology make it a constant signifier for the formation of histories and networks of oppression and otherwise. The representation of water is also neither new nor incidental to Piña-Baldoquín’s work, as he has often featured images of shorelines and sea walls in earlier photo- graphic series.

Manuel Piña-Baldoquín is a Vancouver-based Cuban artist who explores the potential of the vernacular image and urban experience by challenging the dominant narratives that characterize political and cultural nationalism. He studied mechanical engineering in Vladimir, Russia, in the early 1980s before establishing his art practice a decade later. The Cold War legacy of sanctions, political interference and dictatorship in Cuba includes decades of broadcasted images of refugees taking to the seas towards the United States in homemade vessels. This spectacular archive, combined with Piña-Baldoquín’s own migratory routes in pursuit of cultural and academic exchange, serves to nar- rativize the shifting horizons in Naufragios. Furthermore, the implied slippage across watery borders now conjures up the images of refugees fleeing violence in the Middle East and Africa to land on Europe’s southern shores, wading into the spotlight of current international media and political attention.

These mass crossings make visible another temporality. Whether colonial settlers, migrants or slaves, the trans-global flow of bodies across water, borders and boundaries of people creates more than new routes and forums for discursive and cultural geographies. Anthropologist and theorist Arjun Appadurai has argued that ever-shifting cultural flows and networks construct new subjectivities and create “... new communities of sentiment, which introduce empathy, identification, and anger across large cultural distances.” This observation can be expanded upon to consider that such global movements also establish and strengthen cultural identities through new temporal bounds and measures, there- fore claiming time as a subjective entity.

Whether Naufragios puts the viewer in the place of the protagonist about to cross the water, or the perspective of those on land await- ing a welcome or unwelcome arrival, the fact that the human presence is unseen develops the possibility of empathy for either position. The viewer could be looking through the eyes of an Indigenous person of African, American, Asian or other land for whom the sea, that stretch- es out before them, will bring centuries of dispossession, slavery and genocide. The viewer could also be looking through eyes that are contemplating a flight from war and oppression. The viewer may even be looking through the eyes of the would-be colonizer. The only thing that is certain is that the disorientation of both time and space unfamiliar to the protagonist awaits.

Reading Naufragios as an exploration of the multitude of ways that the mass migrations of bodies keeps time also brings to mind Indigenous methods of asserting sovereignty by mapping place through movement and time. In particular, the Stó:lō First Nation entrenches their land rights in history by establishing and tracking the intervals and patterns of the intergenerational migrations of their ancestors and other Coast Salish peoples throughout the Northwest Coast region that traverses the Canadian American border.

Naufragios enacts a reclaiming of subjectivity and sovereignty from the dominant measures of time and time-keeping that have been

universalized through colonization and its attendant technologies. Naturalizing and standardizing his micro time-intervals through association with the assumed truths of geography and topography, Piña- Baldoquín intervenes in standard time codes and describes a counter- time-keeping in line with the various strategies of counter-mapping undertaken by Indigenous, civic and political activists.

Despite the assumed ubiquity of the horizon and the sky upon which Naufragios seemingly depends, both suddenly disappear from the video-work partway through its duration. The frame of the video screen becomes the sole point of visual orientation. The minute-long shifts in shape and pattern continue to establish a rhythm through interlocking triangles then rectangles. The pale sky is replaced with an outright white background. Without the sky, the rippled water dissolves into near- complete geometric abstractions that appear as formalist compositions occupying the screen’s center.

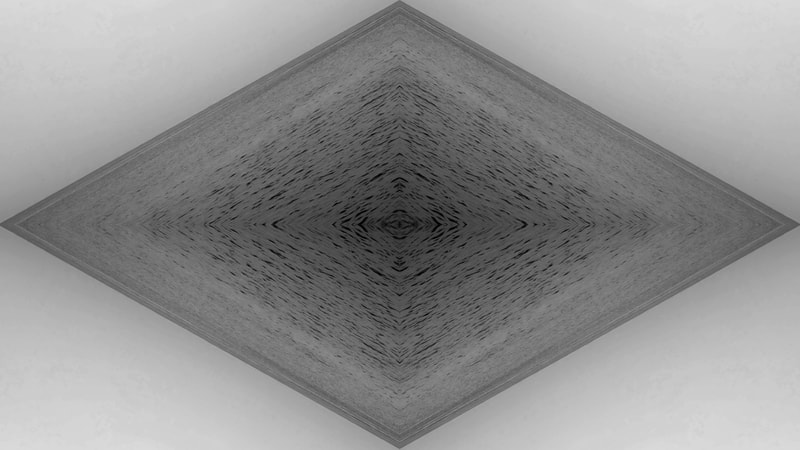

A subtle introduction of colour returns some recognition of a sea- scape into the continuing montage. Squares with sunlight-tipped wave surfaces collide into each other before a sudden return to greyscale and slowed ripples inside a diamond-shaped lozenge. These final frames hypnotize and stretch time while drawing all focus into a central “eye” formed by the surrounding movement. Once this last image relinquishes the viewer’s attention and concludes Piña-Baldoquín’s work, it becomes possible to consider the entire montage that comprises Naufragios.

This work formulates a compelling questioning of the relationship between progress and temporality as represented in the modernist teleos around which frustratingly enduring social histories and dam- aging cultural hierarchies have been structured. The reclaiming of space and bodies dominate the conversation on decolonization, but Naufragios serves as a reminder that the reappropriation and redefinition of temporal structures is an equally effective and necessary act of claiming a sovereign identity.

Throughout much of the 15-minute duration of Manuel Piña- Baldoquín’s 2015 video work, Naufragios, the viewer’s focus is directed towards the liminal visual space where an anonymous body of water meets the sky. Even before encountering Piña-Baldoquín’s work, the viewer is already accustomed to looking towards such horizons as a point of orientation. The artist plays with this visual tendency through a series of digital manipulations, thereby forcing the viewer to repeatedly search the shifting, morphing and folding images for each new horizon.

Naufragios is the Spanish word for shipwrecked, a state of emergency and diversion from the crisscross of global commercial, exploratory and migratory routes that have been established over time. Shipwrecks can lead to the founding of new routes or represent temporary-to- permanent exclusion from the historical and universalized narratives that equate constant movement and expansion with progress. The implied temporariness of Naufragios counters the cultural associations between sea, sky and eternity, and brings the documented seascape in Piña-Baldoquín’s work in line with the series of visual disruptions and glitches that define the formal characteristics of his video.

The opening frames of Naufragios feature a stable image of an anon- replacing the sky save for a narrow, horizontal, light grey band indicating the now doubled horizon. A minute or so more and the sea closes in, filling the sides so that the sky is reduced to a rectangle at the end of a watery tunnel, still pulling the eye towards it.

The video continues like this—now the horizon folds itself into two interlocking right angles, then expands out again to a diamond, with the horizon stretching out towards four corners and referencing the frame of the screen, which slowly overtakes the horizon as the orientating structure. Simultaneously, the time between each shifting form starts to pull away from minute-long intervals to establish a new regularity and unit of time.

The simplicity of Naufragios’ key looping image supports the ease with which Piña-Baldoquín’s forms build on each other to develop a rhythm and timecode unto themselves. The viewer slowly begins to adapt, then rely upon, this shift from the visual orientating structure of the horizon, dividing the water below and the sky above into a new orientational apparatus based on the screen and a series of layered time-intervals.

It is a common association to link water and time through the anonymous body of water. The work is silent and shown in black and white. The horizon line splits the vertical height of the frame at almost the halfway point. The overcast sky and low contrast mostly diminish the visibility of the clouds and juxtapose the seemingly calm sky with the sharp ripples spreading across the dark waters below. The exclusion of visible terrain or any other objects and markers creates a uniform symmetry between sea and sky.

This uniformity allows the viewer to easily spot the jump cuts marking the start of the ten-second loop, from which the video is built. This regular pulsing of the image serves to pull attention away from con-templation of the seascape and towards the characteristics and limits of video as a medium. However, rather than reading as failures, the jumps quickly become familiar and establish the structure of Naufragios. Despite the representations of geography in the recorded image, and the various geometries that Piña-Baldoquín creates from the seascape, it can be argued that Naufragios is a meditation on time rather than space. Beyond engaging video’s time-based qualities, its metronome- like progression proposes that the medium itself can also be a form of time-keeping.

About a minute into the video, the sea suddenly mirrors itself, daily ebb and flow of tides as markers of the passing day. However, Naufragios expands on these broad cultural givens that equate oceans and seas to spans of time, as well as immensities of space and distance. Recent and historical associations between water as a site of migration and mythology make it a constant signifier for the formation of histories and networks of oppression and otherwise. The representation of water is also neither new nor incidental to Piña-Baldoquín’s work, as he has often featured images of shorelines and sea walls in earlier photo- graphic series.

Manuel Piña-Baldoquín is a Vancouver-based Cuban artist who explores the potential of the vernacular image and urban experience by challenging the dominant narratives that characterize political and cultural nationalism. He studied mechanical engineering in Vladimir, Russia, in the early 1980s before establishing his art practice a decade later. The Cold War legacy of sanctions, political interference and dictatorship in Cuba includes decades of broadcasted images of refugees taking to the seas towards the United States in homemade vessels. This spectacular archive, combined with Piña-Baldoquín’s own migratory routes in pursuit of cultural and academic exchange, serves to nar- rativize the shifting horizons in Naufragios. Furthermore, the implied slippage across watery borders now conjures up the images of refugees fleeing violence in the Middle East and Africa to land on Europe’s southern shores, wading into the spotlight of current international media and political attention.

These mass crossings make visible another temporality. Whether colonial settlers, migrants or slaves, the trans-global flow of bodies across water, borders and boundaries of people creates more than new routes and forums for discursive and cultural geographies. Anthropologist and theorist Arjun Appadurai has argued that ever-shifting cultural flows and networks construct new subjectivities and create “... new communities of sentiment, which introduce empathy, identification, and anger across large cultural distances.” This observation can be expanded upon to consider that such global movements also establish and strengthen cultural identities through new temporal bounds and measures, there- fore claiming time as a subjective entity.

Whether Naufragios puts the viewer in the place of the protagonist about to cross the water, or the perspective of those on land await- ing a welcome or unwelcome arrival, the fact that the human presence is unseen develops the possibility of empathy for either position. The viewer could be looking through the eyes of an Indigenous person of African, American, Asian or other land for whom the sea, that stretch- es out before them, will bring centuries of dispossession, slavery and genocide. The viewer could also be looking through eyes that are contemplating a flight from war and oppression. The viewer may even be looking through the eyes of the would-be colonizer. The only thing that is certain is that the disorientation of both time and space unfamiliar to the protagonist awaits.

Reading Naufragios as an exploration of the multitude of ways that the mass migrations of bodies keeps time also brings to mind Indigenous methods of asserting sovereignty by mapping place through movement and time. In particular, the Stó:lō First Nation entrenches their land rights in history by establishing and tracking the intervals and patterns of the intergenerational migrations of their ancestors and other Coast Salish peoples throughout the Northwest Coast region that traverses the Canadian American border.

Naufragios enacts a reclaiming of subjectivity and sovereignty from the dominant measures of time and time-keeping that have been

universalized through colonization and its attendant technologies. Naturalizing and standardizing his micro time-intervals through association with the assumed truths of geography and topography, Piña- Baldoquín intervenes in standard time codes and describes a counter- time-keeping in line with the various strategies of counter-mapping undertaken by Indigenous, civic and political activists.

Despite the assumed ubiquity of the horizon and the sky upon which Naufragios seemingly depends, both suddenly disappear from the video-work partway through its duration. The frame of the video screen becomes the sole point of visual orientation. The minute-long shifts in shape and pattern continue to establish a rhythm through interlocking triangles then rectangles. The pale sky is replaced with an outright white background. Without the sky, the rippled water dissolves into near- complete geometric abstractions that appear as formalist compositions occupying the screen’s center.

A subtle introduction of colour returns some recognition of a sea- scape into the continuing montage. Squares with sunlight-tipped wave surfaces collide into each other before a sudden return to greyscale and slowed ripples inside a diamond-shaped lozenge. These final frames hypnotize and stretch time while drawing all focus into a central “eye” formed by the surrounding movement. Once this last image relinquishes the viewer’s attention and concludes Piña-Baldoquín’s work, it becomes possible to consider the entire montage that comprises Naufragios.

This work formulates a compelling questioning of the relationship between progress and temporality as represented in the modernist teleos around which frustratingly enduring social histories and dam- aging cultural hierarchies have been structured. The reclaiming of space and bodies dominate the conversation on decolonization, but Naufragios serves as a reminder that the reappropriation and redefinition of temporal structures is an equally effective and necessary act of claiming a sovereign identity.

The Photographs of Manuel Piña | By Petra Watson

The idea of mapping the historical landscape depends on the construction of perspective, a view from the present, around which the panoramas of history are made to resolve.1

Unstable identities emerge in Manuel Piña’s mapping of place and historical past: memory assumes the form of the landscape itself. On Monuments (2000) is a series of photographs that comments on the rewriting of history, ideologies, and the obliteration of the past.2 At the end of Spanish colonization and during the American domination of Cuba’s commerce and political relations, the construction of monuments established visual ideological foundations for a new economy and society. In On Monuments, Piña photographed sites where monuments were constructed on Havana’s central boulevard, Avenida de los Presidentes (Avenue of the Presidents), and nearby streets. The monuments (or, in some cases, only proposed commemorative sites) of the series title were statues depicting pre-revolutionary presidents and generals, known for their corruption and pro-American allegiances. These monuments were destroyed during the 1959 Cuban Revolution, leaving only obscure markings, footprints in cement, and empty plinths. “Portraits of sites,” Piña calls these deserted spaces: portraits that present two faces coexisting in an uneasy tension.

Piña presents these now empty sites as a series of discrete markings: an indexical history that is erased. The large colour photographs do not set out to directly reproduce the physical environment of the city, but the landscape that they encounters appear through traces, vestiges, and historical dialogues. In this contingent view, the city lives through remembering. The past is a mobilizing force that engenders a rethinking of the built environment and its social framework, as history is imbedded within the city as an active form, not as disengaged source material.

The eleven photographs that make up the series On Monuments portray a landscape of absence as well as of presence. They do not identify a fixed perception of the city; the images construct narratives that reveal broad cultural, social, and political meanings. The urban environment is read as map and metaphor for both revolutionary ideals and Revolution, and these are seen to take place as much in the shattering of identities as in the construction of them. Piña’s photographs refer to Cuban history through an allegorical reading of the public space of the city and its social-political milieu. The layering of geography and time suggests the process whereby a historical reality is produced, maintained, and altered. As Piña states, “The history of Cuba is the manipulation of evidence and documents.” History, in general, is never disinterested, but operates within terms of authority and legitimation “to produce a narrative sanctioned by power.”3 These portraits of sites hold in balance both the raw materials of history and an urban landscape of displaced memory.

Henri Lefebvre describes “monumental space” as operating within two “primary processes”: first, displacement, “implying metonymy, the shift from part to whole,” and second, “condensation, involving substitution, metaphor and similarity.”4 Monumental space in On Monuments is a metaphorical and quasi-metaphysical underpinning of a society through which the attributes of ideologies are constituted as a dialogue between the people and city landscape. And central to this inquiry into monumentality and power is an exploration of the mechanisms at work behind revolutionary ideals and utopian movements. Revolutionary governance takes place in public, in the piazza and on the street. Havana’s empty public squares, a product of revolution and urbanization, provide only a fragment of vision. Tracing this landscape through cracked cement and empty plinths also comments on the isolated freeze-frame of the photograph itself.

Piña’s approach is to question both ideologically mediated space and the formal concerns of photography played out within an interface between the camera and social/political space. This inquiry began earlier, in a 1996 series of black-and-white photographs (De)constructions and Utopias (Tribute to Eduardo Muñoz). In these small photographs, form is suggestive of content, and each photograph works to “construct” the built environment and “deconstruct” supporting ideologies that result in fragmentation and rupture of social space.

This photographic installation refers to microbrigadas, a building project of the 1980s that attempted to address the housing shortage in Cuba. The government embarked on housing projects in which labour was to be exchanged for an apartment. These projects were halted in 1989, and many remain unfinished. Piña does not directly document social housing, but uses negatives from photographs by Eduardo Muñoz (who documented this building project in the 1980s) to construct history and memory as a utopian moment. He takes these documentary images and, through displacement and substitution, shifts their meaning from fact to fiction, from reality to illusion. Piña writes, The intent of the installation is to convert the room into a utopian space (or its remains). The way the pieces are mounted, their shape and make-up, the variation in tempo, are an attempt to integrate the pieces into the site. . . . I thought it appropriate to use images from the microbrigadas, a popular movement for the construction of housing, because of the close connection between the terms utopia and construction.5

Piña’s appropriated images suggest a “documentary style” that returns the image to the everyday while preserving formal placement as inseparable from the articulation of social/political space and representation.

For Piña, the photographs in (De)constructions and Utopias (Tribute to Eduardo Muñoz) position representation as part of a larger historical framework of inquiry. This approach asks, on the one hand, how the camera might be used for social commentary, and, on the other, how the photographic documentation of social space is focused on the image as index or trace, an event rather than an object, which is far closer to the utopian moment itself. In this way photographs are not interpreted as copying nature; rather, in the transferring of three-dimensional phenomena to a flat plane, the photograph breaks its ties with the real and constructs anew. This is consistent with the idea that utopias are ”sites with no real place,” although they have “a general relation or direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces.”6

In a series of black-and-white photographs from 1992–94, entitled Water Wastelands, Piña photographed Havana’s sea promenade along the Malecon jetty that marks the city shoreline. Images of a broad expanse of water both suggest the history of Cuba as a space of multiple passage – Columbus, Spain, the United States, the Revolution – and provide for a cancellation of this panoramic view. Not set up for a pleasurable stroll along the sea-front promenade, the ocean is a forlorn-looking space within a utopian impulse suggesting both a vast expanse and a dead end. As defined by Piña, this “trauma of space” refers to the actual immigration of Cubans as much as an unrealized utopian notion of “encountering eternity.”7

This is the paradox of Piña’s disconcerting views. The panoramic space of the photographs speaks to these contradictions as both “displacement” and “condensation.”8 Representation thus remains problematic and the viewer of any of these recent photographic series is left not with a descriptive plenitude, but a sense of absence, the emptiness that remains at the centre of ideology and utopia.

Petra Watson is a Vancouver-based curator and public art consultant. She has worked independently and in a number of galleries. She has published extensively and is presently researching panoramic photography from the daguerreotype to the Circuit camera, and its absence from the history of photography. She has studied at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, the University of British Columbia, and Simon Fraser University, where she has a MA in communication (cultural studies), and is a doctoral candidate in interdisciplinary studies.

Notes

1. F. Driver, “Geography’s Empire: Histories of Geographical Knowledge,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Social Space, 10 (1992): 36.

2. Piña exhibited these photographs with Arni Haraldsson in the exhibition Displacement and Encounter: Projects and Utopias, curated by Petra Watson, at the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, an affiliate of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from January 24 to April 7, 2002. This exhibition is travelling to Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, in the fall of 2002. Both artists look at historical conditions that reflect on the present. In a series of images titled The Centre of Paris (1999), Haraldsson photographed the coordinates of Le Corbusier’s unbuilt project the Plan Voisin. Views from the street and from high-vantage points map the city centre that would have been demolished if this project had gone ahead. In part, this feature article extracts from the text panels written for this exhibition.

3. Artist Statement, 2001–02.

4. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford, UK, and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers), p. 225.

5. Quoted in Utopian Territories: New Art From Cuba (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia; Contemporary Art Gallery; and Havana: Ludwig Foundation of Cuba, 1997), p. 104.

6. Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16 (1986): 24.

7. Manuel Piña quoted in Utopian Territories: New Art from Cuba, p. 21.

8. Refer to Lefebvre’s quote above.

Unstable identities emerge in Manuel Piña’s mapping of place and historical past: memory assumes the form of the landscape itself. On Monuments (2000) is a series of photographs that comments on the rewriting of history, ideologies, and the obliteration of the past.2 At the end of Spanish colonization and during the American domination of Cuba’s commerce and political relations, the construction of monuments established visual ideological foundations for a new economy and society. In On Monuments, Piña photographed sites where monuments were constructed on Havana’s central boulevard, Avenida de los Presidentes (Avenue of the Presidents), and nearby streets. The monuments (or, in some cases, only proposed commemorative sites) of the series title were statues depicting pre-revolutionary presidents and generals, known for their corruption and pro-American allegiances. These monuments were destroyed during the 1959 Cuban Revolution, leaving only obscure markings, footprints in cement, and empty plinths. “Portraits of sites,” Piña calls these deserted spaces: portraits that present two faces coexisting in an uneasy tension.

Piña presents these now empty sites as a series of discrete markings: an indexical history that is erased. The large colour photographs do not set out to directly reproduce the physical environment of the city, but the landscape that they encounters appear through traces, vestiges, and historical dialogues. In this contingent view, the city lives through remembering. The past is a mobilizing force that engenders a rethinking of the built environment and its social framework, as history is imbedded within the city as an active form, not as disengaged source material.

The eleven photographs that make up the series On Monuments portray a landscape of absence as well as of presence. They do not identify a fixed perception of the city; the images construct narratives that reveal broad cultural, social, and political meanings. The urban environment is read as map and metaphor for both revolutionary ideals and Revolution, and these are seen to take place as much in the shattering of identities as in the construction of them. Piña’s photographs refer to Cuban history through an allegorical reading of the public space of the city and its social-political milieu. The layering of geography and time suggests the process whereby a historical reality is produced, maintained, and altered. As Piña states, “The history of Cuba is the manipulation of evidence and documents.” History, in general, is never disinterested, but operates within terms of authority and legitimation “to produce a narrative sanctioned by power.”3 These portraits of sites hold in balance both the raw materials of history and an urban landscape of displaced memory.

Henri Lefebvre describes “monumental space” as operating within two “primary processes”: first, displacement, “implying metonymy, the shift from part to whole,” and second, “condensation, involving substitution, metaphor and similarity.”4 Monumental space in On Monuments is a metaphorical and quasi-metaphysical underpinning of a society through which the attributes of ideologies are constituted as a dialogue between the people and city landscape. And central to this inquiry into monumentality and power is an exploration of the mechanisms at work behind revolutionary ideals and utopian movements. Revolutionary governance takes place in public, in the piazza and on the street. Havana’s empty public squares, a product of revolution and urbanization, provide only a fragment of vision. Tracing this landscape through cracked cement and empty plinths also comments on the isolated freeze-frame of the photograph itself.

Piña’s approach is to question both ideologically mediated space and the formal concerns of photography played out within an interface between the camera and social/political space. This inquiry began earlier, in a 1996 series of black-and-white photographs (De)constructions and Utopias (Tribute to Eduardo Muñoz). In these small photographs, form is suggestive of content, and each photograph works to “construct” the built environment and “deconstruct” supporting ideologies that result in fragmentation and rupture of social space.

This photographic installation refers to microbrigadas, a building project of the 1980s that attempted to address the housing shortage in Cuba. The government embarked on housing projects in which labour was to be exchanged for an apartment. These projects were halted in 1989, and many remain unfinished. Piña does not directly document social housing, but uses negatives from photographs by Eduardo Muñoz (who documented this building project in the 1980s) to construct history and memory as a utopian moment. He takes these documentary images and, through displacement and substitution, shifts their meaning from fact to fiction, from reality to illusion. Piña writes, The intent of the installation is to convert the room into a utopian space (or its remains). The way the pieces are mounted, their shape and make-up, the variation in tempo, are an attempt to integrate the pieces into the site. . . . I thought it appropriate to use images from the microbrigadas, a popular movement for the construction of housing, because of the close connection between the terms utopia and construction.5

Piña’s appropriated images suggest a “documentary style” that returns the image to the everyday while preserving formal placement as inseparable from the articulation of social/political space and representation.

For Piña, the photographs in (De)constructions and Utopias (Tribute to Eduardo Muñoz) position representation as part of a larger historical framework of inquiry. This approach asks, on the one hand, how the camera might be used for social commentary, and, on the other, how the photographic documentation of social space is focused on the image as index or trace, an event rather than an object, which is far closer to the utopian moment itself. In this way photographs are not interpreted as copying nature; rather, in the transferring of three-dimensional phenomena to a flat plane, the photograph breaks its ties with the real and constructs anew. This is consistent with the idea that utopias are ”sites with no real place,” although they have “a general relation or direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces.”6

In a series of black-and-white photographs from 1992–94, entitled Water Wastelands, Piña photographed Havana’s sea promenade along the Malecon jetty that marks the city shoreline. Images of a broad expanse of water both suggest the history of Cuba as a space of multiple passage – Columbus, Spain, the United States, the Revolution – and provide for a cancellation of this panoramic view. Not set up for a pleasurable stroll along the sea-front promenade, the ocean is a forlorn-looking space within a utopian impulse suggesting both a vast expanse and a dead end. As defined by Piña, this “trauma of space” refers to the actual immigration of Cubans as much as an unrealized utopian notion of “encountering eternity.”7

This is the paradox of Piña’s disconcerting views. The panoramic space of the photographs speaks to these contradictions as both “displacement” and “condensation.”8 Representation thus remains problematic and the viewer of any of these recent photographic series is left not with a descriptive plenitude, but a sense of absence, the emptiness that remains at the centre of ideology and utopia.

Petra Watson is a Vancouver-based curator and public art consultant. She has worked independently and in a number of galleries. She has published extensively and is presently researching panoramic photography from the daguerreotype to the Circuit camera, and its absence from the history of photography. She has studied at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, the University of British Columbia, and Simon Fraser University, where she has a MA in communication (cultural studies), and is a doctoral candidate in interdisciplinary studies.

Notes

1. F. Driver, “Geography’s Empire: Histories of Geographical Knowledge,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Social Space, 10 (1992): 36.

2. Piña exhibited these photographs with Arni Haraldsson in the exhibition Displacement and Encounter: Projects and Utopias, curated by Petra Watson, at the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, an affiliate of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from January 24 to April 7, 2002. This exhibition is travelling to Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, in the fall of 2002. Both artists look at historical conditions that reflect on the present. In a series of images titled The Centre of Paris (1999), Haraldsson photographed the coordinates of Le Corbusier’s unbuilt project the Plan Voisin. Views from the street and from high-vantage points map the city centre that would have been demolished if this project had gone ahead. In part, this feature article extracts from the text panels written for this exhibition.

3. Artist Statement, 2001–02.

4. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford, UK, and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers), p. 225.

5. Quoted in Utopian Territories: New Art From Cuba (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia; Contemporary Art Gallery; and Havana: Ludwig Foundation of Cuba, 1997), p. 104.

6. Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16 (1986): 24.

7. Manuel Piña quoted in Utopian Territories: New Art from Cuba, p. 21.

8. Refer to Lefebvre’s quote above.

Past exhibition at Mónica Reyes Gallery

Manuel Piña | AFTER ALL (2020)

Installation view of Manuel Piña | After All | 2020

The initial premise of this exhibition involved (potentially endless) playlists of YouTube and Vimeo videos generated by their respective algorithms; a sequence of all the images ever posted to Instagram, Facebook and other social media and, lastly, an endless scroll of Giphy.com homepage. The result would be an infinite collage, a collectively-authored, ever evolving Image with contributions across the Globe, a true Image of the Present.

What would such Image reflect from us?

What would it reveal about what we are today?

Where is the hope, the truth of the world?

What is, at last, going on?

While Anything and Everything's Possible, that initial idea proved a daunting task thus Piña has opted for a mere snapshot: an algorithm-generated curation of YouTube videos, and his own contributions to such collective creation.

What would such Image reflect from us?

What would it reveal about what we are today?

Where is the hope, the truth of the world?

What is, at last, going on?

While Anything and Everything's Possible, that initial idea proved a daunting task thus Piña has opted for a mere snapshot: an algorithm-generated curation of YouTube videos, and his own contributions to such collective creation.

|

MANUEL PIÑA

shares this video as comment on the COVID-19 situation from Vancouver, BC. April 13, 2020 |

|

Past institutional exhibitions

Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago

MUSEUM OF LATIN AMERICAN ART

LONG BEACH | CALIFORNIA | USA

SEP 16,2017 - JAN 28,2018

Condemned to be Modern

LOS ANGELES MUNICIPAL ART GALLERY

LOS FELIZ | LOS ANGELES | CALIFORNIA | USA

SEP 10,2017 - JAN 28,2018

Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950

WALKER ART CENTER

MINNEAPOLIS | MINNESOTA | USA

NOV 11,2017 - MAR 18,2018

Cuba and The Bahamas. Contemporary Art from the Caribbean

HALLE 14

LEIPZIG | GERMANY

APR 29,2017 - AUG 06,2017

Ficción y Fantasía – Art from Cuba

DAROS EXHIBITIONS, LATINAMERICA

ZÜRICH | SWITZERLAND

SEP 11,2015 - DEC 13,2015

Beyond the Supersquare

BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS

BRONX | NEW YORK | USA

MAY 01,2014 - JAN 11,2015

Manuel Piña: Like a Dirty Joke or an Angel

MARVELLI GALLERY

CHELSEA | NEW YORK | USA

NOV 03,2011 - DEC 17,2011

Changing the Focus: Latin American Photography (1990-2005)

MUSEUM OF LATIN AMERICAN ART

LONG BEACH | CALIFORNIA | USA

FEB 13,2010 - MAY 02,2010

MUSEUM OF LATIN AMERICAN ART

LONG BEACH | CALIFORNIA | USA

SEP 16,2017 - JAN 28,2018

Condemned to be Modern

LOS ANGELES MUNICIPAL ART GALLERY

LOS FELIZ | LOS ANGELES | CALIFORNIA | USA

SEP 10,2017 - JAN 28,2018

Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950

WALKER ART CENTER

MINNEAPOLIS | MINNESOTA | USA

NOV 11,2017 - MAR 18,2018

Cuba and The Bahamas. Contemporary Art from the Caribbean

HALLE 14

LEIPZIG | GERMANY

APR 29,2017 - AUG 06,2017

Ficción y Fantasía – Art from Cuba

DAROS EXHIBITIONS, LATINAMERICA

ZÜRICH | SWITZERLAND

SEP 11,2015 - DEC 13,2015

Beyond the Supersquare

BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS

BRONX | NEW YORK | USA

MAY 01,2014 - JAN 11,2015

Manuel Piña: Like a Dirty Joke or an Angel

MARVELLI GALLERY

CHELSEA | NEW YORK | USA

NOV 03,2011 - DEC 17,2011

Changing the Focus: Latin American Photography (1990-2005)

MUSEUM OF LATIN AMERICAN ART

LONG BEACH | CALIFORNIA | USA

FEB 13,2010 - MAY 02,2010